“One staircase led to heaven the other to hell” says Robert Carrithers of a building in New York’s St. Mark’s Place Street, number 57. The building whose basement housed, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Club 57 – a creative laboratory for all non-conformists and free-thinkers from the East Village – actually belonged to the central offices of the Polish Catholic Church.

At that time New York was a city on the verge of bankruptcy and today’s luxurious East Village resembled a war zone. Refined citizens had long ago left the area as part of a progressive suburbanisation. The area with burnt up brick buildings – a last ditch attempt by desperate property owners to earn some money was more than often insurance fraud – was left in the hands of drug dealers, immigrants and also artists working in all disciplines. The police didn’t even bother to patrol there, which was good for anyone annoyed by having the authorities riding their back, artists and criminals alike. “It was often a matter of life and death. You had to have eyes in the back of your head and constantly watch what was happening in the street. It was so intense that sometimes you would find a corpse lying on the sidewalk,” recalls Carrithers, who moved to New York from Chicago in 1979. He wanted to study photography, film and acting there. The apartment that he could afford to rent was less than a 10-minute walk from Club 57.

The punk and disco scenes concentrated around the CBGB and Studio 54 clubs were losing their sense of novelty and originality, when out of nowhere a performer like Klaus Nomi appeared. This was a man, who sang opera in the costume of a Dutch Pierrot. Club 57 was in fact founded by two friends, who loved vaudeville – Susan Hannaford and Tom Scully – and was run by director and performer, Ann Magnuson, who hosted its first performance.

“This place was fascinating in that, while artists had earlier met in bars or at concerts, they chatted and they drank, but in Club 57 they created something together. Here concerts mixed with exhibitions and performances,” stresses Carrithers, when speaking of the community that first made him feel at home. Ann Magnuson thought up theme parties for every other night of the week. She found the decor and the furniture in the streets. Keith Haring had his first installation there and created his signature work, as did Kenny Scharf and Jean Michel Basquiat.

Club 57 exorcised America’s evil spirit. It went wild from “camp” aesthetic. With a Dadaistic fascination and vigour, it seized on the suburban supermarket culture; stores that had become museums of the contemporary lifestyle and its plastic kitsch. During one evening a country-western evening might take place on piles of hay, the next a burlesque event and an Elvis memorial, then a performance showing John Sex performing with his python snake Delilah or a concert by singer, Wendy Wild, and her group, The Mad Violets, which took the public on a joint trip, when hallucinogenic mushrooms were thrown into the crowd. The group, Pulsallama, was also born here. This was a group of twelve or thirteen girls, who sang in the style of Greek chorales, and when doing so banged on beer bottles, pans, cowbells and shot off kids‘ toy machine-guns. Pulsallama made it so far that in 1982 they were the opening act at several concerts by The Clash.

Even almost thirty years after its closing in 1983, Club 57 is still a legend that defined a period of pop culture and still inspires it. Many of the artists tied to the institution were unable to face up to their own wildness, drugs or the incontrollable rise of AIDs. They died. Others died only to become immortal (Haring, Basquiat). Others survived to become famous later (Ann Magnuson, Marc Shaiman, Scott Whitman).

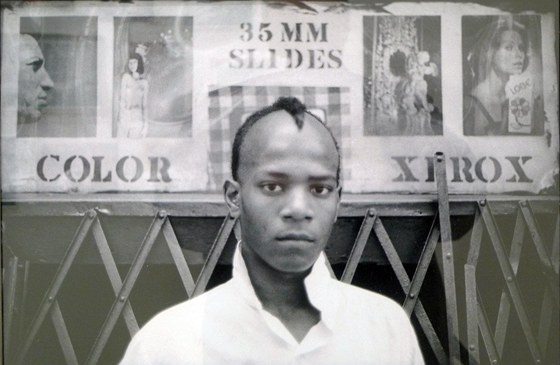

Robert Carrithers was one of them. He spontaneously documented everything that happened in the club. The performances, the birth of success, the first exhibitions and the backstage area. In his moment shots and portraits, which will be shown for the first time in the Czech Republic, barmen meet with writers, film-makers and future celebrities. Thus a unique testimony was created; one that is as unbridled image-wise as the Club 57 program.

Robert Carrithers is an American photographer and film-maker, who lives in Prague. Besides the Club 57 scene he documented the post-November cultural scene in the Czech Republic and has been working for a long time on the series, Bohemian Nude. He is preparing a documentary on the Prague-Berlin-Australian, post-punk band, Fatal Shore. Its members include Phil Shoenfelt, Bruno Adams (died in 2009) and Chris Hughes. Besides their common devotion to music, each member of the band also married a Czech woman.

He also took part in the making of the documentary Autoluminescent about the Australian musician Rowland S. Howard (dir. Richard Lowenstein), for which he shot all European interviews and concert footage. Rowland S. Howard (died 2009), an icon of alternative rock, was a member of bands like The Birthday Party, Crime and the City Solution or These Immortal Souls.

Carrithers‘ next documentary project is dedicated to a woman named, Koy, who for seventeen years now has been living in Japan and working with local musicians there. Due to serious illness she has planned her own funeral for the sixth of May this year. She wants to attend the event herself and say good-bye to all her friends. After finishing these projects, Carrithers plans to shoot an erotic horror comedy, which takes place in Prague.

Pavel Turek

Guests at the opening: DJ Miki, Mark Steiner & His Problems, a showing of films of Cinema of Transgression by Nick Zedd