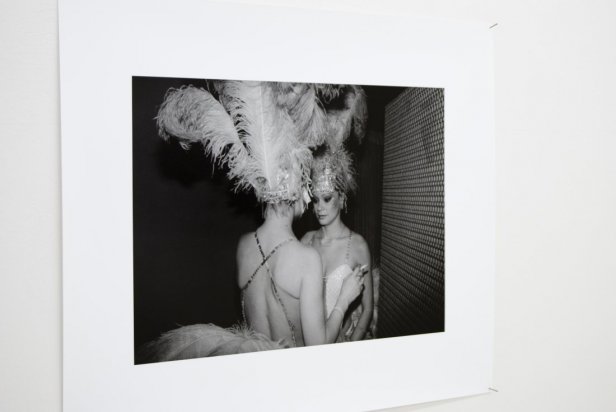

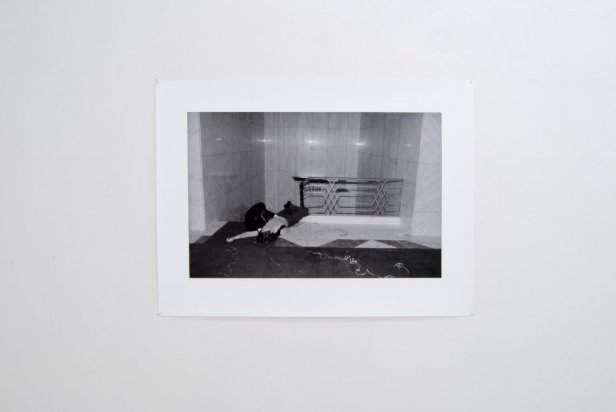

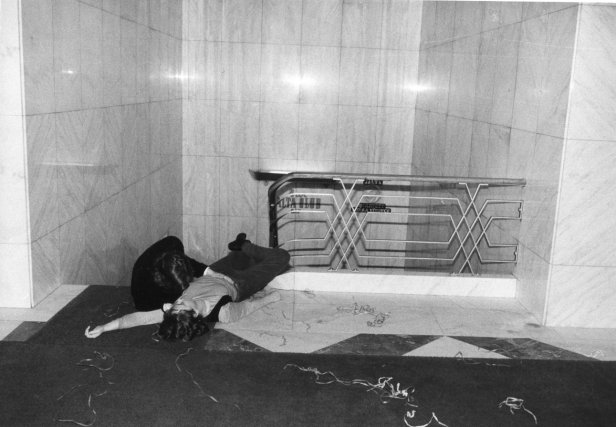

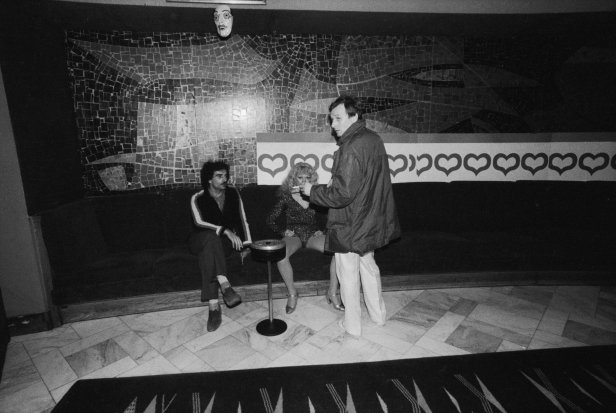

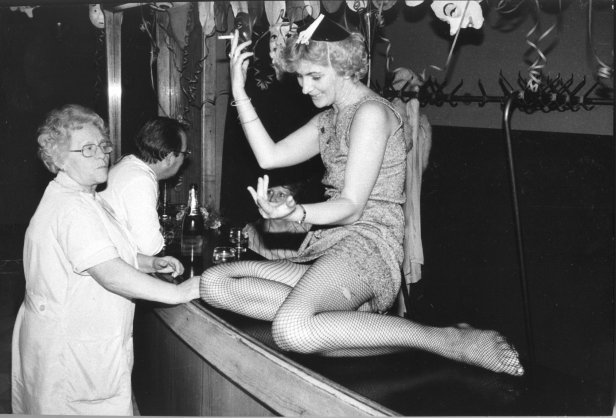

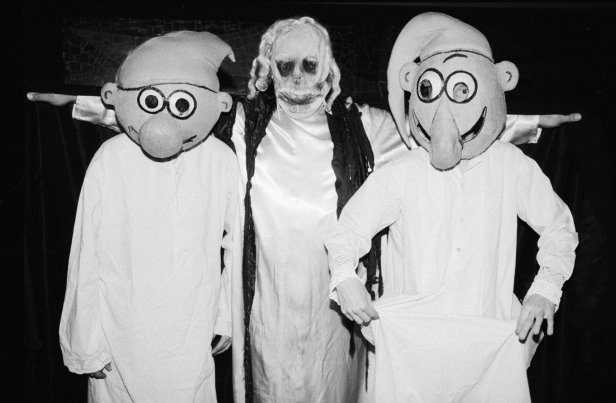

Viktor Kolář’s Ostrava, Jindřich Štreit’s village, views of the street from Jiří Hanke’s flat, Iren Stehli’s shop windows, Jaroslav Bárta’s pavements and windows, the Czech Man (Český člověk) Project – all of them suggestively put a name to Czech society in the 1980s. They are conveniently complemented by photographs of New Year’s Eve parties at the Yalta Hotel taken by Jan Jindra, a FAMU student at that time, for a mock-up for a school publication. Among other things, they marked a departure from the Czech documentary tradition that had been dominated by the consistent use of natural light without using a flash, an attempt at naming social relationships, and a positive, or at least benevolent, point of view. In his harsh flash shots without any added visual embellishments, Jindra places more emphasis on coldness and hopelessness, similar to the approach used by Libuše Jarcovjaková, who, during the same timeframe and just a few metres away, photographed the famous T-Club, a meeting place for the gay and lesbian community. During a short period covering the two New Year’s Eves between 1982 and 1984 Jindra captured orgiastic celebrations taking place literally beneath the paving stones of Wenceslas Square, celebrations that offered a special mix of broad-mindedness, poor taste, erotica and alcohol; and a diverse range of performances, including illusionists and routines by characters from Czech fairy tales, all accompanied by one of the very few striptease acts that existed in the then-Socialist environment of Czechoslovakia. In the self-proclaimed egalitarian society of that time, Jindra photographed the boisterous happiness of the representatives from the nobility of that time, deserving Communist Party members, company directors and managers as they mingled with the Wenceslas Square subculture that existed back then: cab drivers, black marketeers, and ladies of the night. He identified phenomena that did not officially exist in Socialist Czechoslovakia. In the 1980s, the media never offered a negative image of society and the visual images presented to the public were very different. Amongst other things, this exhibition makes it impossible to avoid asking whether one can extract from these photographs what attracted the attention of their viewers at that time. At least a hint of what the answer might be can be seen in the viewpoint of Petr Balajka, who shortly after the creation of the photo series writes: ‘Jindra’s photo documentary from the New Year’s Eve parties held at the hotel provides convincing proof of how interpersonal relationships were disrupted in our country; it portrays the solitariness of the individual and how difficult it was to be spontaneous and to find one’s own identity.’

Tomáš Pospěch