Roughly three years ago Jan Nálevka (*1976) began to address the conceptual proposals of the artistic avant-garde from the first half of the 20th century. The offering of his new artistic language, meant to motivate people to realize radical societal change, appeared to be another option for his conceptual paraphrasing of the term “office work.“ In a trio of his works put together for his exhibition at Fotograf Gallery he thus touches upon phenomena such as voluntary suppression of individuality for the good of the collective whole, adhering to and fulfilling standards and norms or exhausting labor in contradiction with the promise of liberation.

For his works that build on a constructivist morphology and ideological proclamations by the architects and theoreticians, Ladislav Žák and Jiří Kroha, the artist had to count on their being viewed as (socially) engaged. It’s easy to imagine them being both positively accepted and rejected – both by opponents of “social engineering“ as well as among those who, due to their disgust with the current state of capitalism, are calling for the political demands of the leftist avant-garde to be re-evaluated. Nálevka’s objective is, however, to remain outside the polarizing space of this debate. In a certain sense he has chosen the worst of these possible stances, a sort of disassociation from either side. As a creative artist he is interested most in the option of rewriting; or perhaps more exactly: the draping of one net of meaning over another net of meaning.

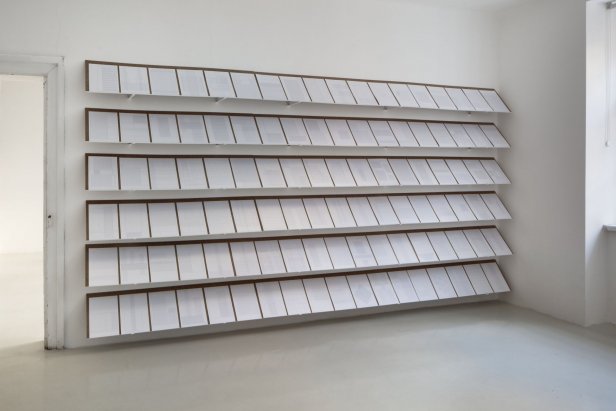

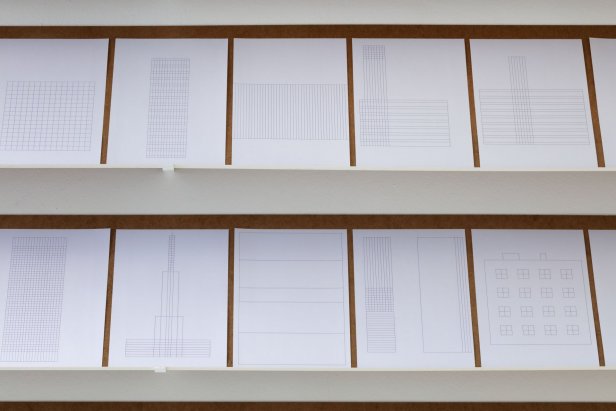

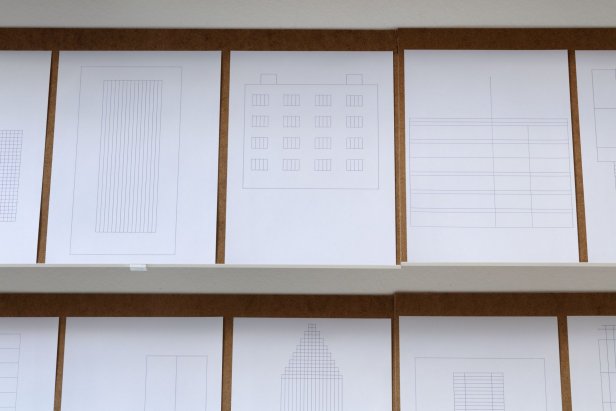

He expresses this most precisely in his description of his newest collection of sketches Form follows the norm (2016), where he writes that his “aim was to create sketches morphologically on the boundary between architecture and blanks.“ It’s necessary to add, however, that the right-angle net he chose is once again (defined by Nálevka for the umpteenth time) firstly a norm for grid paper and edges of an A4 sheet of paper. Secondly, it’s a number of pages of a certain weight in a standard sold package. “Variations on an architectural theme“, evoking the composition of the new, pre-war architecture (and its reverberations and renaissance), are meant to make the level of the technocratic solution for a given task more visible. It does so for a dual type of suppression of individual contributions for the benefit of results that have been requested by or which are good for the collective whole.

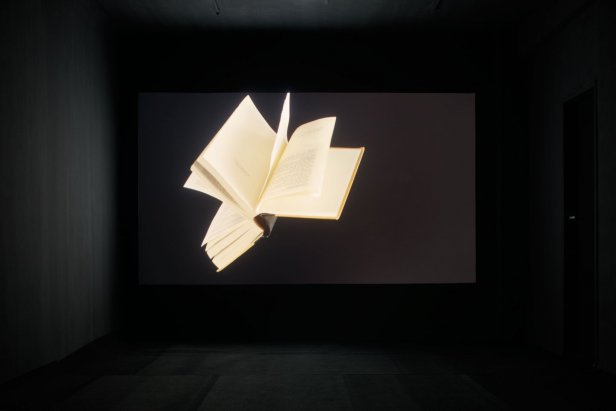

In his oldest video-projection (chronologically) with the overly-long title, By the use of automatic machines to the leisure time, culture material and spiritual, human selfimprovement, health, tranquility, peace, inner life and liberation in the freed, saved, renewed and freshly created nature of renaturalized landscapes (2013), Nálevka focuses most of his attention on the language of propaganda. For this work, he bought a quartet of short video clips from a commercial image bank; one accessible for representatives of a world of idealized, pandering images. The selection of images was meanwhile determined by a diagram from Ladislav Žák’s book, The Inhabited Landscape (1947), whose accompanying text served Nálevka as the work’s title. Even here the contradiction between the aims of a leftist theoretician and hedonistic strategies of late capitalist visual productions is not important. More relevant is harmony with the romanticizing pathos that is meant to fascinate and convince us.

In the last of the three collections, sketches on photocopies of reproductions of the well-known The Sociological Housing Fragments of Housing (1932), initiated and associated with the personality of architect and leftist theoretician, Jiří Kroha, gather motives from both of the aforementioned realizations. These “instructional“ panels classified or structured people’s living conditions based on class. Nálevka covered them with a regular net of sketched out lines that match the format of graph paper. In the collection, Fragment (2015), we meanwhile find its predecessor in the same type of overlapping photocopies of books, Thoughts of Modern Sculptors (2013). If, however, these older drawings could be interpreted as preparation of the paper for further use (otherwise stated: as acquiring a surface for writing new chronicles on the fine arts through the outdated construction of art history from books published in Czechoslovakia during the 1970s), then we can perceive Fragment in the context of the exhibition, A New Definition of Progress, as a further attaching of norm to norm. Nálevka’s hand-made copy of a machine print once again demands suppression of creative arbitrariness and submission. Thus without any psychological implications we can claim that for all three of the exhibited collections we come across the topic of erasing subjectiveness and its submergence in various time periods (and historic eras) as norm connected to form.

Jiří Ptáček