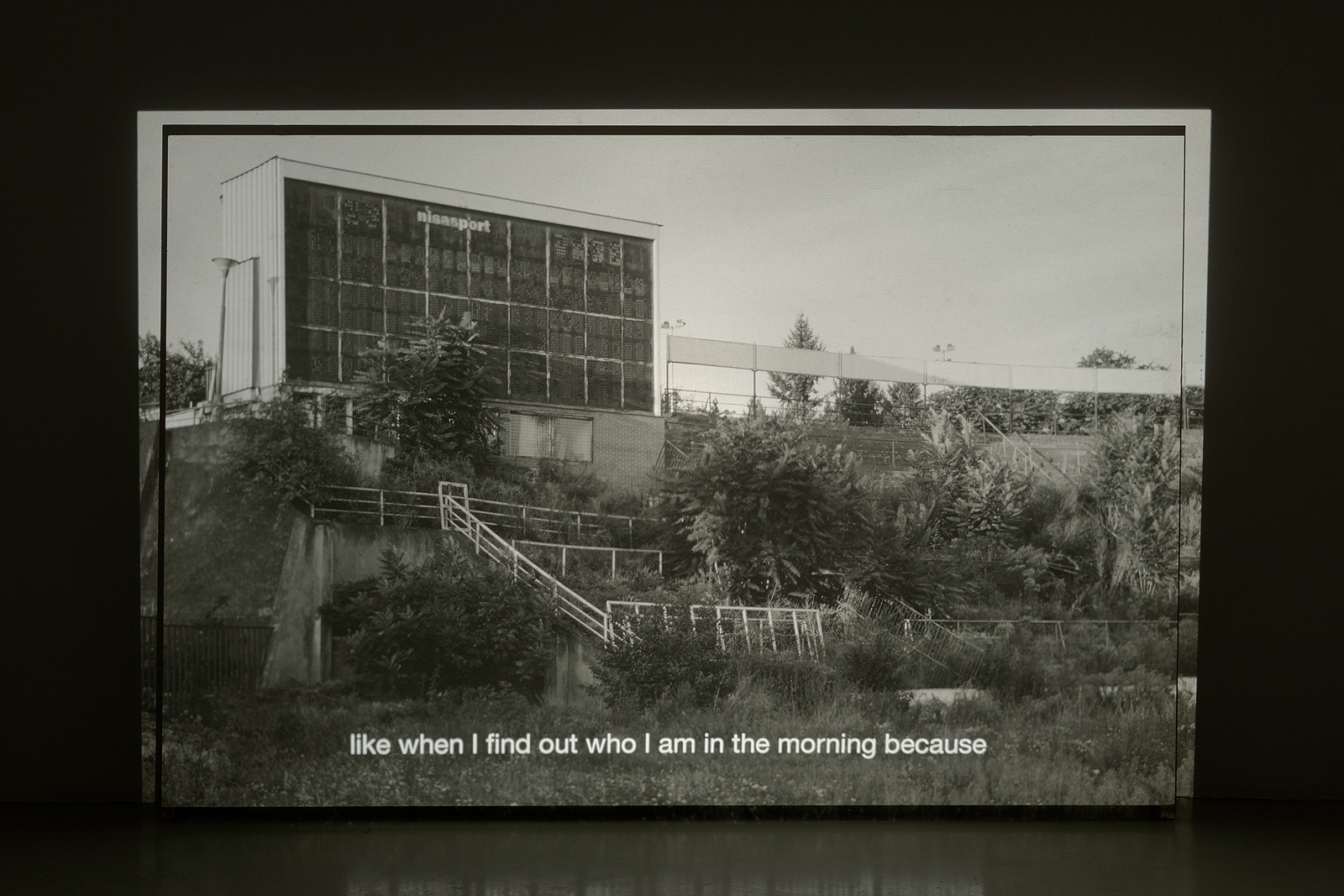

Empty playgrounds and stadiums are impressive places. When athletes are not chasing one another around their surfaces and cheers are not coming from the stands, they turn into a wasteland. Because they are built for people to gather in them, for movement and desire (sweat and the roar of crowds), the view of human absence creates a feeling of lacking. This feeling is a powerful catalyst for another movement, imagination. „It’s sad. Especially when I think back on how in the 1980s we celebrated winning a championship here, or when in the 1990s tens of thousands of viewers still came here. I even played here when I was young,“ a man once told a reporter from the news server, idnes.cz, who was writing an article about the unused and grass overtaken football stadium in Brno’s Lužánky district. Photographs of this stadium are the image component of Filip Cenek’s two-channel projection.

It’s characteristic that even Austrian, Josef Dabernig, never photographed any of the flash-filled, architecturally imposing, „billion dollar“ arenas. He visited empty stadiums and playgrounds during his travels to Eastern and Southern Europe, to Northern Africa, Turkey and to the Caucasus. When looking at their photos, it’s as if our attention jumped over the empty surfaces without action and clung to the edges, where after all something exists. Walls, stands, goal posts, living quarters on-site …. The central emptiness creates a contrasting tension with the full edges, similar to the courageous stadiums on the periphery (edges) of the mammoth club and Olympic sporting grounds.

Dabernig generally stood himself on the half-way line and with his digital camera shot „panoramas“ consisting of six parts. He did not join the photos in a row, but rather presented them as a line of neighbouring images. So much for the general parameters of his method. It is good to summarise them that way, for during more detailed observation we mainly come across deviations and seams. The basic typological framework of the six photos is disrupted as is the central axis as the starting point for taking pictures. It would also be impossible to align the photos in a unified panorama, because the captured segments are not contiguous. So it will be difficult to give the table installations sufficient distance for viewing the whole. It’s as if Dabernig’s intention were asymmetry and confusion. Provided we can compare the viewing of his photos to an adventure, then this is only because of the tension between established and more lax rules. The stadiums are empty, but still it’s as if their photographic representation were ruminating over the methodical dogma that one could cling to in their interpretation. The process of emptying thus becomes part of the viewers’ experience in his series; an experience that they needn’t internally accept, but which they cannot escape.

His colleague, who’s a generation younger, Filip Cenek, projects from one carousel a sequence of photographs of the overgrown Lužánky stadium and from a second one text. This is another of his two-channel slide projections, in which the image and the text take on a changing role against one another. No matter how film-maker, Josef Dabernig, with his photographic panoramas has for years touched on filmability (and creating panoramas that are sought after ex post as a sort of Australopithecus of film), for Cenek film narration is the basic starting point of the differentiated use of archival and binding elements in the language of film in asynchronous, non-linear compositions. Similar to Dabernig the tension is based on the awareness of basic, conceptual grids (in his case, on the awareness that the ordering of images and texts is determined by a programmed algorithm) that predetermine their own fluidity. In Cenek’s slide projections image and word meet up differently each time (for example, it needn’t be easy to follow this); they are distinct in their narrative structures and dependent on this they also create distinct associational environments.

Jiří Ptáček

Josef Dabernig (1956) works in Vienna. He studied sculpture and in addition to that he works with texts, film and architectural installations. His work has received high international acclaim, demonstrated by the long line of independent exhibitions he has done and his participation in film revues. In the Czech Republic his work has been shown at the Brno gallery, Na bidýlku, at the Moravian Gallery in Brno, and at projections by tranzit.cz in Prague’s Světozor Cinema. Dabernig underscored his exceptionally fond relationship to the Czech people by shooting his film, Herna (2010), in Brno. Filip Cenek played one of the roles in this film.

Filip Cenek (1976) works in Brno. Last year he was a finalist for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award. He runs the Video Studio at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno and is an assistant at the Inter-media Atelier. He is co-initiator of the freelance collective, Fiume, at the Faculty of Fine Arts. Dozens of curatorial films and exhibitions have been created under this brand, as well as live music-image performances and also several DVDs and publications. Parallel to their joint exhibition at the Fotograf Gallery, they will present another area of their work – an audio-visual collaboration with Ivan Palacký – in the exhibition area at the Školská 28 Communication Space.